"The existence of a common psychic substratum explains why analogous mythological motifs and symbols can be found in religions of all ages and in places very far apart. The point is that these archetypal patterns (such as, for example, the motif of the death and resurrection of the hero, or the symbol for wholeness as represented by the mandala) have not been made by man, nor are they in the first instance due to diffusion, cultural influences or education. Instead, such constellations of ideas have over an immense period of time evolved and become rooted in the depth of the human psyche from where they spontaneously arise even - or perhaps especially - when the conscious mind is inactive and in need of introspection. All our conscious actions, thoughts, imaginations and religious practices have developed from the substratum of these unconscious archetypal images, and they will always remain connected with them.

Viewing the decorated caves of the Palaeolithic period, we may perhaps be tempted to think of these early artists as 'them' versus 'us', the 'primitive' as contrasted to the 'modern' man. Such simple distinctions are, however, deceptive because as

homo sapiens we not only have the same psychic substratum but also the same brain structure. The supposition therefore that so-called 'primitive' man thought or experienced his world in a way that was significantly different from us is not based on fact. True, our consciousness is far more developed than that of our forebears and we may justifiably think of ourselves as modern. All the same, we cannot escape the fact that there is another life in us, one that from our higher but lopsided rational position we either cannot or no longer want to see: our prehistoric past. According to Jung, 'every civilized human being, however high his conscious development, is still an archaic man at the deeper levels of his psyche.' This being the case, what is it then that distinguishes our psychology from that of Ice-age man?"

The Descent into the Cave by Dr. Ilse Vickers

http://www.bradshawfoundation.com/cave_art_an_intuition_of_eternity/decent_into_the_cave/index.php

This is a snippet of an interesting article I stumbled on that shows promise, tying together some of Jung's work on archetypes as applied to Ice Age cave paintings.

It continues:

"Briefly, in primitive man the conscious mind is as yet hardly differentiated from the unconscious. We assume that he still lives in a primordial state and in total harmony with his surroundings; he is so tuned in that he can hear the 'voice' of his mountains, his woods, his rivers, etc., and know, for example, when the weather will turn long before it actually happens. Primitive man still has what the French philosopher Levy-Bruhl (1857-1939) termed, a participation mystique, a mystical relationship or identification with his world. As studies into primitive societies that have survived to the present have shown, primitive man is convinced that not only human beings but animals and even objects have a spirit, a soul or a voice, and that all he has to do, is find the right wood, the right piece of land, or rock, etc., and he will hear the voice. Unlike modern man who has learnt to differentiate between the subjective and the objective, primitive man is unable to make such a distinction; for him the subjective and the objective are fused in the external world."

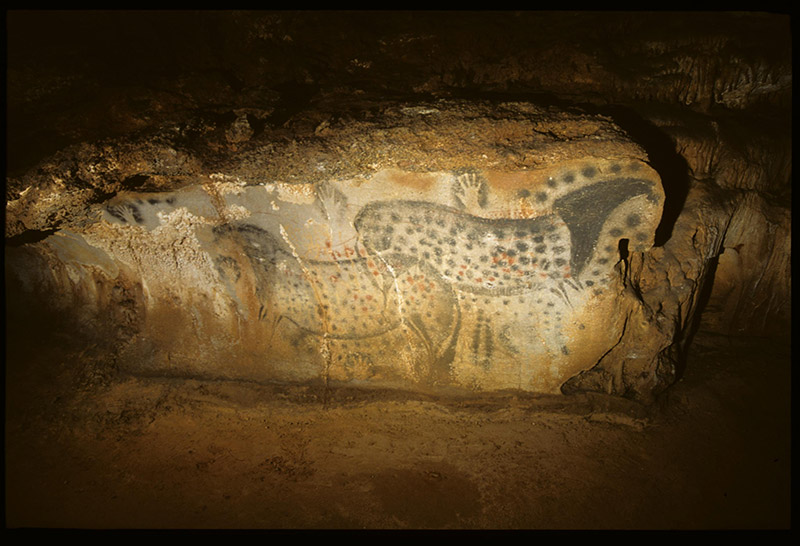

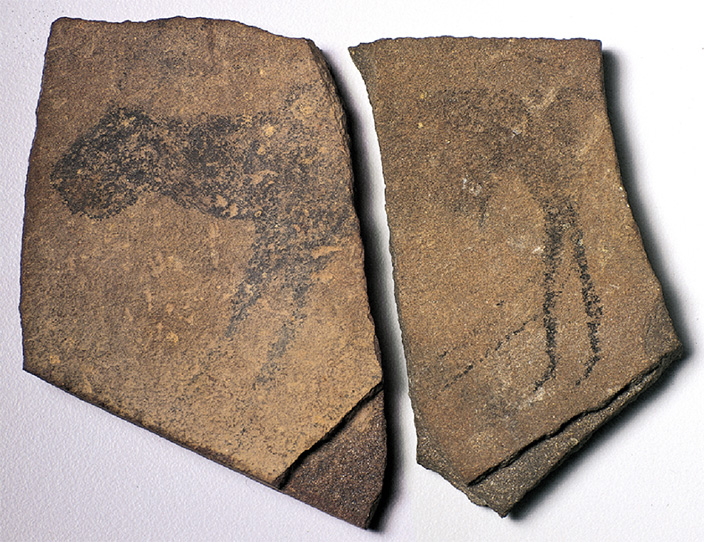

"Assuming that the cave paintings were depictions made by shamans following such ecstatic experiences, the cave paintings may be seen to reflect the visionaries' mystical experience. Moreover, since the psychological experience springs from the deep layers of the unconscious concerned not with the personal but with the universal, collective problems of humankind, the paintings are of archetypal nature. The remarkable thing is not that the shamans of the Palaeolithic had the visions they did but that they accepted them as divinely or externally inspired, and that accepting them they translated them into mortal form, the art of their rock paintings. The visions captured in the form of paintings seem to point to a higher, archetypal truth. Rather than giving individual stories, they tell of man's intimate relationship with nature, of his understanding of the coming and going of the seasons and the animal herds, and of man's role as hunter that he has played since time immemorial. Perhaps one of the reasons why the paintings communicate such a sense of wholeness is that they are not man-made but divinely-given masterpieces - man was not their creator; he was the emissary of the creation."

" As soon as we try and dissect the Palaeolithic cave paintings and state that they either mean this or that, we have unravelled the precious and complicated weave of strands, and their true meaning is lost: their treasure lies in their totality. Psychologically speaking, the rock paintings of Ice-age man, like the mystery cults, indeed like all the great religious belief systems are not a matter of the intellect but a psychic experience which expresses itself in symbols. The unconscious - because it is unconscious - can only communicate and be communicated in the form of symbols, visions, dreams, and metaphors. The symbolic language of the unconscious is at the same time a most primitive language, arising from the remote, bestial instinctive spheres of our being, and it is also the language which gives man insights of the highest order, far beyond what our rational mind could produce by itself."

"One can try to replace symbols and the religious experience which they carry with science but to do so may be an impoverishment: symbols are like a treasure chest and harbour an immense wealth of age-old insights. Moreover, no science will ever be able to create or replace the archetypal language of man's visions as we find them expressed in the form of the arts. No science will ever be able to explain why we feel entranced by the Palaeolithic cave paintings; why they have the power to move us, address our deepest hopes and fears, and help us to momentarily transcend our human limitations."

"It appears that modern, 'civilized' man's highly differentiated consciousness has come at a price. Modern man's inward path is made difficult by the demands for explanation, logic, justification, profit, use, effect, and so on. However, those willing to push past these obstacles, those with the stamina to brave the downward-inward journey to the unchartered regions of the mind will, like Palaeolithic man, find the 'right' spot, the place of penetration, where all opposites fuse in the divine spark of creation."