Online article:

http://www.bradshawfoundation.com/clottes/human_animal_activities.php

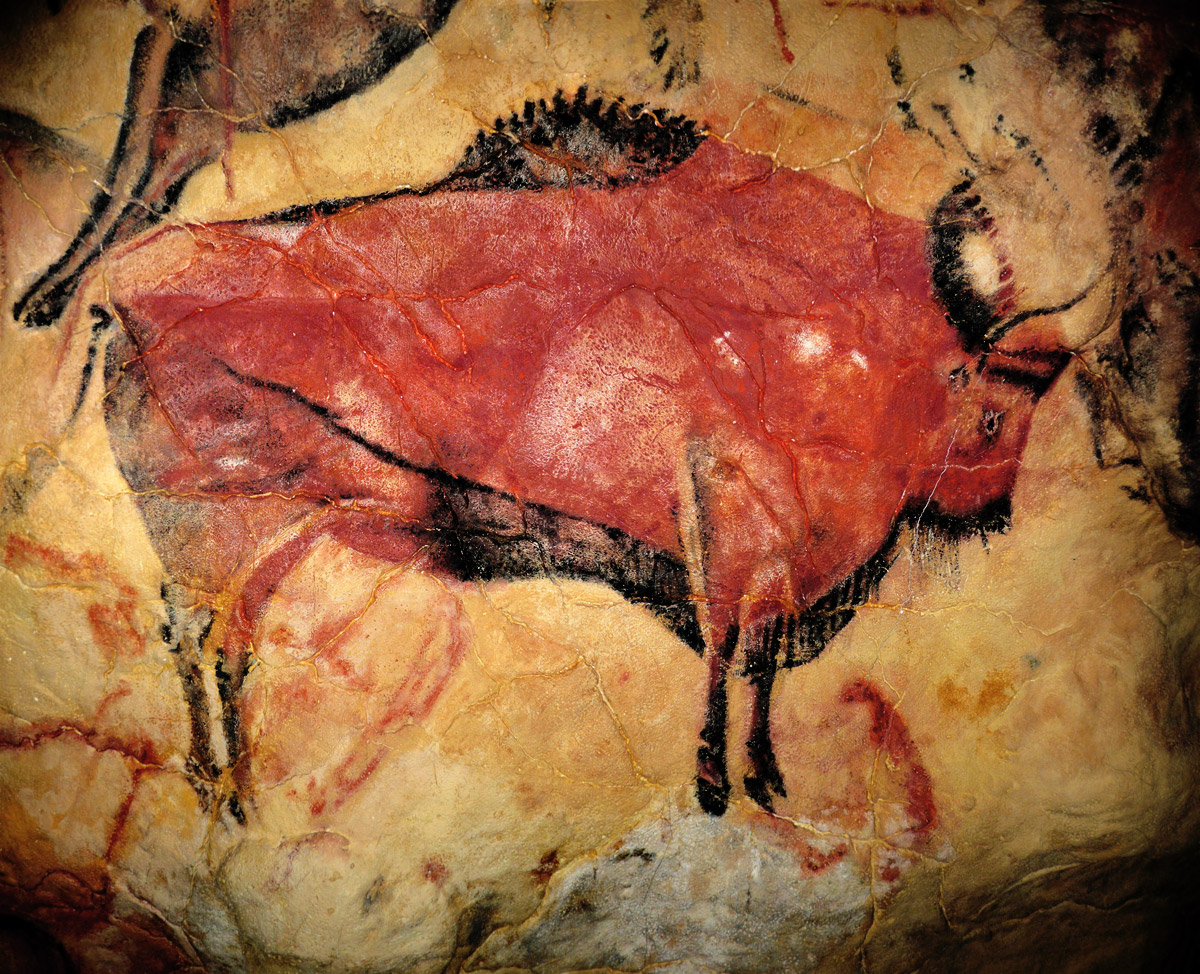

"Paleolithic wall art cannot be dissociated from its archaeological context. This means the traces and remains of human and animal activities in the deep caves are valuable clues about the actions of their visitors, and are better preserved in them than in any other milieu.

Bears, particularly cave bears, hibernated in the deepest galleries. Some died and their bones were noticed by Paleolithic people when they went underground. At times they made use of them : they strung them along the way and lifted their impressive canines in

Le Tuc d’Audoubert; in Chauvet, they deposited a skull on a big rock in the middle of a chamber and stuck two humerus forcibly into the ground not far from the entrance. Cave bears scratched the walls as bears do trees and their very noticeable scratchings may have spurred people to make finger tracings (

Chauvet) or engravings (Le Portel).

Humans left various sorts of traces, whether deliberately or involuntarily. When the ground was soft (sand, wet clay), their naked footprints remained printed in it. (

Niaux, Le Reseau Clastres, Le Tuc d’Audoubert, Montespan, Lalbastide, Fontanet, Pech-Merle, L’Aldlene, Chauvet). This enables us to see that children, at times very young ones, accompanied adults when they went underground, and also that the visitors of those deep caves were not very numerous because footprints and more generally human traces and remains, are few.

The charcoal fallen from their torches, their fires, a few objects, bones and flint tools left on the ground are the remains of meals or of sundry activities. They are also part of the documentation unwiittingly left by prehistoric people in the caves. From their study, one can say that in most cases painted or engraved caves were not inhabited, at least for long periods. Fires were temporary and remains are relatively scarce. Naturally, there are exceptions (Einlene, Labastide, Le Mas d’Azil, Bdeilhac). In their case, it is often difficult to make out whether those settlements are in relation - as seems likely - or not with the art on the walls. The presence of portable art may be a valuable clue to establish such a relationship.

Among the most mysterious remains are the objects deposited in the cracks of the walls and in particular the bone fragments stuck forcibly into them (see also below). After being noticed in the Ariegie Volp Caves. (Enlene, Les Trois- Freres,

Le Tuc d’Audoubert) (Begouen &

Clottes 1981), those deposits have been found in numerous other French Paleolithic art caves (Bedeillhaic, Le Portel, Troubat, Erberua, Gargas, etc.). They belong to periods sometimes far apart, which is not the least interesting fact about them because this means that the same gestures were repeated again and again for many thousands of years. Thus, in Gargas, a bone fragment lifted from one of the fissures next to some hand stencils was dated to 26,800 BP, while in other caves they are Magdalenian i.e. more recent by 13,000 to 14,000 years.

The Gravettian burials very recently discovered in the Cussac cave (Aujoulat et al. 2001) pose a huge problem. It is the first time that human skeletons have been found inside a deep cave with Paleolithic art. Until they have been excavated and studied properly it will be impossible to know whether those people died there by accident (which is most unlikely), whether they were related to those who did the engravings, whether they enjoyed a special status, etc. Their presence just stresses the magic/religious character of art in the deep caves."