path_of_one

Embracing the Mystery

So let's compare the early humans, starting with H. erectus, the first human that was substantially like us (i.e., of a normal-tall height, with a large brain, and that thought to travel out of Africa).

Homo erectus was around from about 1.8 million years ago to about 200,000 years ago, and she managed to be the first one to leave Africa, traveling all over the lower part of Asia throughout Indian and China, and down to some areas that are now islands in upper southeast Asia but were (back then during the Ice Age) connected by land bridges. H. erectus was also throughout the Middle East and of course Africa, and some speculate in Europe (but no clear evidence at this point).

The interesting cultural features that arise with H. erectus are that she used fire (though it is not likely she manufactured it), there is evidence that there may have been organized stampedes to get meat (no evidence of large-game hunting, though), and that he came up with the Acheulian tool kit, the most famous and prevalent tool being the hand ax. I've held hand axes over a million years old in my grubby little paws. It was pretty cool to think of holding an antique from some dude that was so much like me yet so unlike me.

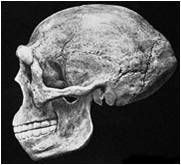

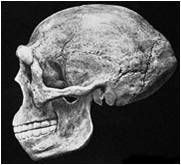

Anyhoo, they obviously had some very new and interesting changes going on compared to H. habilis. Not only did they have all these new cultural things going on, they had physical changes too. They were much, much bigger than H. habilis- they were slightly taller than we are today. Their brains exploded in size, reaching an average of 985 cc (compared to our avg of 1350 today). Yet... they still were really different from us. Their bodies show that they most likely had the vocal tract of an ape, not like ours. They had practically no forehead.

Debates around if they had language center on how difficult it is to teach hand ax making. That's about the most difficult thing they did, with the possible addition of organizing a stampede. Could they have learned hand ax making through observation, and visual instruction? Do you have to have language to stampede, or can you point to a herd and a cliff? There is no indication among H. erectus that there was higher level thinking. They did live in groups, but there are no burials, no art, no evidence of even making clothing (though of course they must have had skins because it was freezing in Asia at the time). So, most people think language (at least in its complex, spoken form) is unlikely for H. erectus. However, it is highly probable that the beginnings of group cooperation with gestures and some sound would have been the norm, given the activities. We currently don't know why they left Africa; population pressure was unlikely. Perhaps that was the first glimmer in the human mind of wanting to explore, of having a goal, of thinking in new ways about the world around them.

Homo erectus was around from about 1.8 million years ago to about 200,000 years ago, and she managed to be the first one to leave Africa, traveling all over the lower part of Asia throughout Indian and China, and down to some areas that are now islands in upper southeast Asia but were (back then during the Ice Age) connected by land bridges. H. erectus was also throughout the Middle East and of course Africa, and some speculate in Europe (but no clear evidence at this point).

The interesting cultural features that arise with H. erectus are that she used fire (though it is not likely she manufactured it), there is evidence that there may have been organized stampedes to get meat (no evidence of large-game hunting, though), and that he came up with the Acheulian tool kit, the most famous and prevalent tool being the hand ax. I've held hand axes over a million years old in my grubby little paws. It was pretty cool to think of holding an antique from some dude that was so much like me yet so unlike me.

Anyhoo, they obviously had some very new and interesting changes going on compared to H. habilis. Not only did they have all these new cultural things going on, they had physical changes too. They were much, much bigger than H. habilis- they were slightly taller than we are today. Their brains exploded in size, reaching an average of 985 cc (compared to our avg of 1350 today). Yet... they still were really different from us. Their bodies show that they most likely had the vocal tract of an ape, not like ours. They had practically no forehead.

Debates around if they had language center on how difficult it is to teach hand ax making. That's about the most difficult thing they did, with the possible addition of organizing a stampede. Could they have learned hand ax making through observation, and visual instruction? Do you have to have language to stampede, or can you point to a herd and a cliff? There is no indication among H. erectus that there was higher level thinking. They did live in groups, but there are no burials, no art, no evidence of even making clothing (though of course they must have had skins because it was freezing in Asia at the time). So, most people think language (at least in its complex, spoken form) is unlikely for H. erectus. However, it is highly probable that the beginnings of group cooperation with gestures and some sound would have been the norm, given the activities. We currently don't know why they left Africa; population pressure was unlikely. Perhaps that was the first glimmer in the human mind of wanting to explore, of having a goal, of thinking in new ways about the world around them.